Scene:

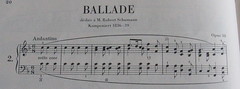

a very elegant room, perhaps a suite, in an exclusive metropolitan hotel; a grand piano seems out of place near the French windows; other furniture crowds away from it; Evgeny Kissin sits at a small table set for breakfast; another cup of strong black coffee is stealthily poured for him; on the table, a music score or two peeks from beneath various foreign newspapers; Kissin balances one on his knee and seems to study a particular article with great intent.

[

Enter Kissin's manager, excitedly waving dailies.]

MANAGER: Good reviews, great reviews! They all still love you! From

Washington to

New York, you're still

it! [

Reading aloud various comments, ad lib] "stunning," "a marvelous Chopin interpreter," "great sensitivity and organic development," "an ironclad technique."

KISSIN [

unfazed]: Hmmm.

MANAGER [

taking a seat]: To have [

he gestures like a pianist] "a technique that serves a greater musical idea" [

trailing off and then, a PAUSE.] It makes me think [

happy expression wavering for a split second] about next season. Maybe... well... [

clears throat, peers a few times into an empty coffee cup] I think people--critics, too--would love to hear how you play something other than Chopin. Just for a season, of course.

KISSIN [

with brows slightly furrowed]: Hmmm.

MANAGER: Sophia Gubaidulina, for example. She's got a Sonata, some short pieces, a Toccata, I think. You'd be a natural at her style, and performances of her music are rare. People would be excited, no?

KISSIN [

sips coffee]: Hmmm.

MANAGER: Or the North American Ballads of Frederic Rzewski; they're really an extension of Chopin, of that sort of romantic piano writing. To hear you dig your fingers, your interpretive talents, into something so "American," it could be really interesting, give the critics some new lines. C'mon, I'm not suggesting Boulez or, god forbid,

Bussotti.

KISSIN [

finally looking up from the paper]: Yes, I too was thinking. Of the B-flat minor sonata. Of Chopin.

MANAGER [

trying not to frown]: More Chopin? Really? [

Hums the famous "funeral march" theme with dramatic exaggeration.] It's just that, [

breaking a buttery croissant into shards and setting the pieces down, unwanted] do you ever think that maybe you have a responsibility to venture beyond this repertoire? With your abilities, your [

reading aloud] "star appeal," you could reshape, reinvent the classical piano recital, break down some

stereotypes.

[

Kissin arches one eyebrow.]

MANAGER [

continuing undeterred]: I just hate to think of you in this pigeonhole, of going down in the history books as [

reading] "the last great Romantic virtuoso." Chopin in practice, sure, a place for you to continue refining your skills. A sort of exercise, right? But in performance? It's so a hundred years ago, [

even more excited, with a growing sense of conviction] it's holding you back! What about

your time? Right now? And the future? What speaks to and of you, now, in 2005?

KISSIN [

in a tone that could level buildings]: The B-flat minor caused a critical commotion, you know. It wasn't what everyone

expected from a sonata. That word, "sonata," had for some become just a predictable template, a [

with a scolding glance] pigeonhole, with certain arrangements of notes and movements, and opus 35 did not fit. It surprised. I find that conflict--between the piece itself, and its

reception--interesting. And then to find in the musical conflict, in the notes and harmonies, moods and evocations, the forward vision. Chopin, using the model, relying on it, but not trapped by some mere definition. I appreciate that [

pausing] irony. People will not "get it." It is difficult.

MANAGER [

not getting it]: Riiiiight. [

There is a PAUSE.] Chopin. Sure no Rzewski? Gubaidulina? [

Taking great delight in a mouthful of vowels] How 'bout Ustvolskaya? [

With voice deepening, then puffing up] certainly there is a...difficulty...in some of those works as well.

KISSIN [

pulling the score from the pile of newspapers, stands up and walks toward the piano]: Chicago. I was thinking I'd like to play Chicago, maybe Prague. Chopin wrote the piece in France, in the countryside one summer. Perhaps Paris in June...the Paris audience is always such a challenge.

MANAGER [

morosely pushing at the pieces of croissant]: I'll get on that right away. [

He stands abruptly.]

[

Exit the manager, with a lingering glance at the newspapers on the table. As the scene dims to a close, someone can be heard humming "Down by the Riverside."]

continue reading...