From the Ether

Certain pieces announce their intentions within the opening measures of music. Most of Beethoven's symphonies, for example. Mozart's Magic Flute. Even, I would argue, the prelude to Tristan and Isolde, or Steve Reich's Clapping Music. The initial "hello" contains the whole composition. Though musical development and departures unfold, (and in fact, the listener almost expects something unexpected) on subsequent hearings we knowingly recognize the entire work, in its distilled or condensed form, in those opening chords, rhythmic motifs, or outlined intervals.

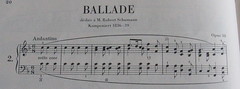

Other music begins from the ether, with little suggestion of what lies ahead. Even after years of knowing and having performed a particular piece, one might say, dumbstruck, "Oh! It starts like that?" Every time I see that first line of Chopin's Second Ballade, for example, I do a double take. From such simplicity--a moment of minimalism on C, way before its time--the lullaby begins. The first phrase is almost enough--more than enough--to build a pleasant piece of Romantic parlor music. Yet not too many bars later, Chopin launches into a tirade, cuts short the lullaby, and lets the fun begin; the fine finger muscles of the technical pianist tell the ear of the voicing artist to move over, and we leave the parlor for the concert hall. Music literature offers numerous examples of such compositional design, of course, but for some reason the Ballade never--never--fails to tip me off my seat, whether I'm playing or listening to it.

People are like this, too, no? Some put it all out there (call it openness or honesty) from that first handshake, while others, a friend you've known for ten years maybe, can surprise the pants off you with an out-of-character action. I find both types equally likable and infinitely frustrating. I often want more from the obvious ones (surprise me! give me steak when I'm expecting chocolates!) but find that the outbursts of the more kept ones throw me off guard or make me feel I've been led on. Those are the rewards and challenges of socializing, I guess. So too with music: it takes all kinds, from the familiar to the freak, to make life fun.

1 Comments:

Here's something rather wonderful that Adorno said about Chopin:

"Chopin's form is no more concerned with the development of the whole through a series of minute transactions than with the representation of a single free-standing thematic complex. It is as remote from Wagner's dynamic thrust as form the landscape of Schubert. For all that it still contains the inherent contradiction that dominates the whole of the 19th century, the contradiction, namely, between the concrete specificity of the parts and their abstract, subjectively posited totality. He masters this contradiction by removing himself, as it were, from the flow of the composition and directing it from the outside He does not high-handedly create the form, nor does he allow it to crumple before the onslaught of the themes. Rather, he conducts the themes in their passage through time. The aristocratic nature of his music may reside less in the psychological tone then in the gesture of knightly melancholy with which subjectivity renounces the attempt to impose its dynamism and carry it through. With eyes averted, like a bride, the objective theme is safely guided through the dark forest of the self through the torrential river of the passions. Nowhere more beautifully then in the A-flat ballade, where the creative idea, once it has made its appearance like a Schubert melody, is taken by the hand and conducted through an infinite vista of inwardness and over abysses of expressive harmonics where it finds its second confirming appearance. In Chopin paraphrase and doubtless every kind of associated virtuosity in the resigned expression of historical tact."

--Martin

By Heather Heise,

at 8:37 AM

Heather Heise,

at 8:37 AM

Post a Comment

<< Home